Case Scenario: Cardio–Hepato–Renal Syndrome with Oligo-anuric AKI requiring early RRT

Posted by Dr KAMAL DEEP on January 11, 2026

An 80-year-old woman with a long history of hypertension presented with progressive shortness of breath, markedly reduced urine output, and bilateral pedal edema over several days. She had been on chronic antihypertensive therapy with amlodipine and losartan and was taking aceclofenac daily for many years for chronic musculoskeletal pain. There was no history of recent hypotension or overt shock.

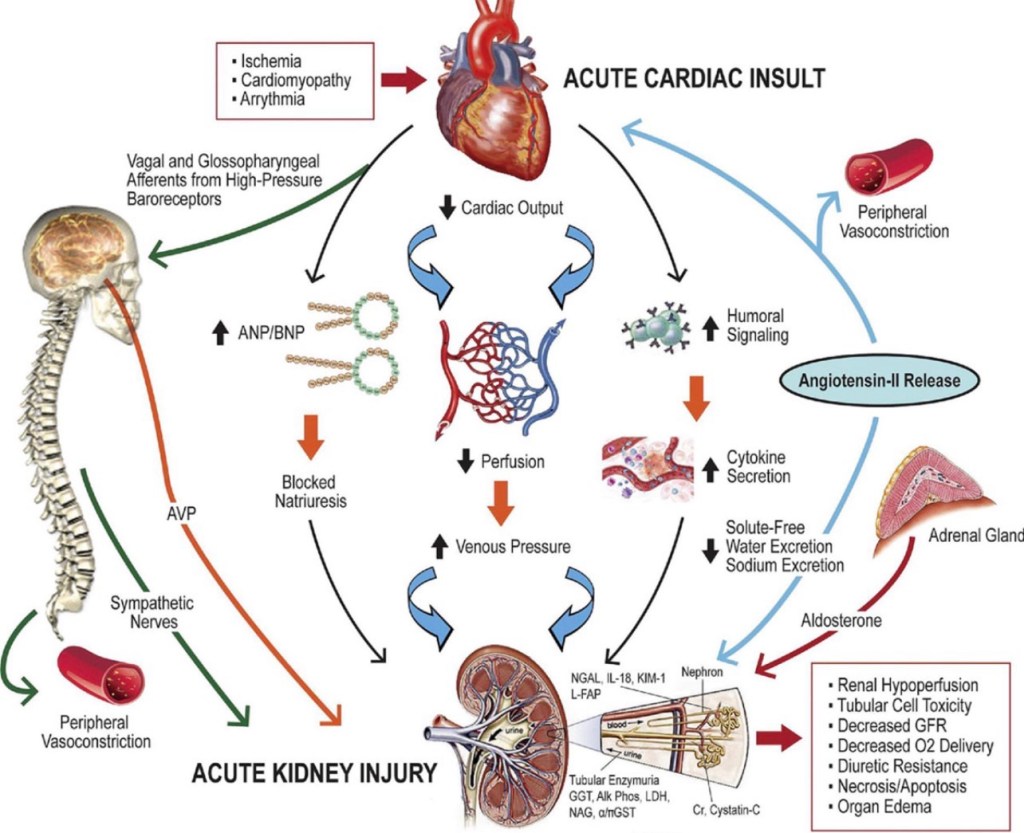

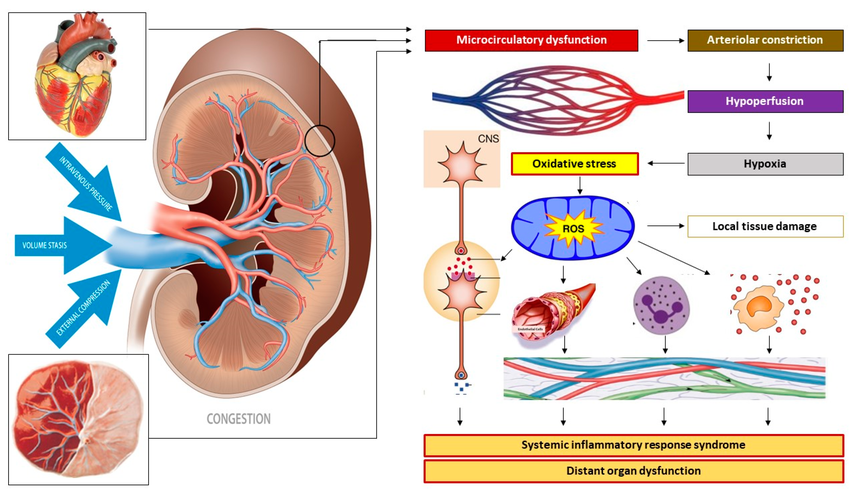

Mechanisms of venous congestion at the level of the kidney. Venous congestion can result from venous vascular hypertonia with subsequent venous hypertension, from volume stasis arising from (sub-)obstructed outflow, and/or from external compression. At the level of the kidneys, this congestion induces a retrograde dysfunction of the peritubular and glomerular capillaries. Reflex arteriolar constriction and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system prevents further microcirculatory deterioration at the cost of reduced organ perfusion and subsequent parenchymal hypoxia. An oxidative stress response induces immunological, neurological, and metabolic protection mechanisms by activating the autonomic nervous system and the intravascular distribution of cytokines, endocrines, and vasoactive mediators, causing endothelial activation and a generalized state of inflammation. In non-pregnant individuals, this sequence of events unfolds in the kidneys as part of the pathophysiology of renocardial syndrome but can also occur in other internal organs as in cardiohepatic or hepatorenal syndromes. In pregnancy, this mechanism may unfold in the uterus and placenta as well as in internal organs. In this picture, the kidney may serve as a proxy for other maternal organs, such as uterus-placenta, heart, etc.

On examination, she was conscious, oriented, and hemodynamically stable, but tachypneic with bilateral basal crepitations and significant peripheral edema. Urine output was severely reduced. Laboratory investigations revealed serum creatinine 5.6 mg/dL, total leukocyte count 15.6 ×10⁹/L, and a markedly elevated procalcitonin of 50 ng/mL, suggestive of severe sepsis.

Ultrasound abdomen showed features of chronic kidney disease with chronic liver disease and ascites. CT chest demonstrated cardiomegaly with pulmonary congestion, consistent with fluid overload.

The presentation was interpreted as acute oligo-anuric AKI on CKD, occurring in the setting of acute cardiorenal syndrome. Long-standing hypertensive heart disease had resulted in diastolic dysfunction (HFpEF), leading to pulmonary congestion and renal venous congestion, thereby reducing effective renal perfusion. Superimposed chronic NSAID use caused prostaglandin inhibition with afferent arteriolar constriction, while chronic losartan therapy resulted in efferent arteriolar dilation. The combined effect of reduced inflow, increased outflow, and elevated venous back-pressure led to collapse of glomerular filtration pressure, explaining the patient’s oligo-anuria and poor diuretic responsiveness.

The associated chronic liver disease was attributed to long-standing hepatic venous congestion (congestive hepatopathy) secondary to chronic cardiac dysfunction, likely accelerated by recurrent subclinical hypoperfusion and long-term NSAID exposure, completing a cardio-hepato-renal syndrome. Given severe oligo-anuria, fluid overload with respiratory compromise, and sepsis-associated ATN, the patient was planned for early renal replacement therapy as physiologic support rather than rescue therapy.

Teaching point:

Mechanisms of venous congestion at the level of the kidney. Venous congestion can result from venous vascular hypertonia with subsequent venous hypertension, from volume stasis arising from (sub-)obstructed outflow, and/or from external compression. At the level of the kidneys, this congestion induces a retrograde dysfunction of the peritubular and glomerular capillaries. Reflex arteriolar constriction and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system prevents further microcirculatory deterioration at the cost of reduced organ perfusion and subsequent parenchymal hypoxia. An oxidative stress response induces immunological, neurological, and metabolic protection mechanisms by activating the autonomic nervous system and the intravascular distribution of cytokines, endocrines, and vasoactive mediators, causing endothelial activation and a generalized state of inflammation. In non-pregnant individuals, this sequence of events unfolds in the kidneys as part of the pathophysiology of renocardial syndrome but can also occur in other internal organs as in cardiohepatic or hepatorenal syndromes. In pregnancy, this mechanism may unfold in the uterus and placenta as well as in internal organs. In this picture, the kidney may serve as a proxy for other maternal organs, such as uterus-placenta, heart, etc.

Leave a comment